|

![]()

Greatest Films of the 1940s

1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949

Title Screen Film Genre(s), Title, Year, (Country), Length, Director, Description

La Belle et La Bete (1946, Fr.) (aka Beauty and the Beast), 96 minutes, D: Jean Cocteau

This fanciful and enchanting story has been remade many times, both as short silent and talkie versions, and most memorably as Disney's animated film in 1991. Writer/director/painter-poet Jean Cocteau produced this as his first feature film, and asked the audience as the film started: "I ask of you a little . . . childlike simplicity." It was adapted from a classic 1757 fairy tale by French novelist Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont, the story of how commoner Belle/Beauty (Josette Day) saved her father (Marcel André) by giving herself to a repulsive Bete/Beast (Jean Marais). The major theme was finding beauty beneath outward appearances, told with some obvious Freudian symbolism and haunting, surreal and atmospheric images. The magical and visually-beautiful film began with an introduction to the four siblings of a family now destitute due to the failure of their father's merchant shipping business. There were two wasteful, spoiled, haughty, evil and vain sisters: Adélaïde (Nane Germon) and Félicie (Mila Parély), and the hard-working, enslaved and devoted Belle. The fourth sibling was their lazy wastrel brother Ludovic (Michel Auclair), who protectively sheltered Belle from the romantic pursuits of his handsome friend - the shallow scoundrel Avenant (also Jean Marais). One dark night in the forest when returning home after a failed business trip, the father was taken prisoner in an extravagant and magical palace castle by the resident angry and grotesque half-man, half-Bete - for the crime of taking one rose bush blossom. He was given the choice within three days of dying himself, or having one of his three daughters replace him. The self-less and childlike Belle chose to take her father's place and sacrifice herself as a hostage, but soon found that her repulsive-looking captor treated her with kindness, politeness and riches. Slowly, she began to develop an affection for the cursed and virile Bete, who met her every evening at 7 in the dining room, and asked to marry her. When she left for a few days to attend to her sick father, she found the Bete dying (of heartbreak) upon her tardy return. He was transformed, and a spell was broken, when she expressed deep sorrow and love for him. He was now a charming Prince (also Jean Marais), while Avenant now came under the spell as the new Bete. In the film's happily-ever-after conclusion, the transformed Beast - now a new Prince - revealed that a fairy had cursed him, because his parents didn't believe in fairies. Belle and the Prince returned to the castle by flying. They were to live there, with the father and her sisters, who would now serve her.

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), 172 minutes, D: William Wyler

William Wyler's landmark, classic drama, and Best Picture-winning film was both powerful and provocative, with many touching moments in the lives of combat survivors now returned to their former lives, with both hopefulness and poignancy - attempting readjustment to peacetime life and discovering that they had fallen behind. The lengthy film featured great acting, story-telling, direction and pacing by Wyler. It was based upon the 1945 novella "Glory for Me" by MacKinlay Kantor. It was perhaps the most memorable film about the aftermath of World War II, unfolding with a number of great plot threads about the homecoming of three servicemen to their small town. The compassionate movie portrayed the reality of altered lives, readjustments at work, dislocated marriages and the inability to communicate the experience of war on the front lines or the home front. This was the first picture for Harold Russell, a non-actor and war veteran who was an actual amputee, who won two Oscars for the same role (a unique achievement) - Best Supporting Actor, and a Special Honorary Oscar "For bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans through his appearance..." In the film's opening set in the nose of a B-17 bomber, three returning veterans had their first glimpse of their (fictional) hometown of Boone City - feeling alienated, aloof and detached from the strange sights and memories of their former home - and attempting readjustment to peacetime life and discovering that they had fallen behind. The three WWII veterans were: middle-class husband Army Sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March), a former Cornbelt Bank banker who turned to drinking, decorated Air Force Captain Fred Derry (Dana Andrews) who was rejected by his unfaithful war-bride spouse Marie Derry (Virginia Mayo) and was forced to return to his old job as a soda-jerk, and handicapped seaman Homer Parrish (Oscar-winning Harold Russell) who had lost both arms and agonized over his relationship with his childhood sweetheart-girlfriend Wilma Cameron (Cathy O'Donnell). In the film's most poignant moment, Homer's mother (Minna Gombell) experienced her first look at her double-amputee son's hooks for hands, and had an uncontrollable reaction. During his deeply-moving homecoming reunion scene, Sgt. Al Stephenson entered his apartment complex and then the door of his apartment and silenced with his cupped hand the mouths of his son Rob (Michael Hall) and daughter Peggy (Teresa Wright) - and then suddenly, his wife Milly (Myrna Loy) was surprised to realize that he had come through the door. Fred experienced PTSD - fitful, sweaty nightmares of a disastrous bombing run over Germany, while Peggy (a trained nurse) comforted and soothed him. Persistent and young Peggy Stephenson, Al's intelligent, articulate, headstrong daughter, made some remarkable homewrecking efforts to win Fred away from his mismatched marriage to his unloving blonde floozy wife Marie Derry. Another of the most remarkable scenes was of Fred Derry's walk through a junked airplane graveyard where he relived his many wartime memories of bombing missions in the nose of an abandoned B-17 bomber. The film concluded with Homer's wedding to Wilma, when he demonstrated great skill in placing a ring on her finger - with the added knowledge that Peggy and Fred - seen in the background - would eventually also marry after his divorce with Marie could be finalized.

The Big Sleep (1946), 114 minutes, D: Howard Hawks

Howard Hawks' and Warner Bros.' classic atmospheric film noir mystery with crackling dialogue was based upon Raymond Chandler's first novel in 1939. Its incomprehensible plot (and tortuous story line without a completely clear resolution) was scripted by William Faulkner (with Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett). It set the standard for private detective movies, and was remade in 1978 with Robert Mitchum. The film's title was a reference to death. In the film's opening, down-at-the-heels, tough LA private investigator Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart). was hired by General Sternwood (Charles Waldron), a dying, invalid millionaire, to look into various issues that led to drugs, nymphomania, pornography, decadence and murder. Marlowe's main task was to prevent a blackmailer from collecting debts from Sternwood that had been incurred by the old man's indiscreet, thumb-sucking, unstable nymphette youngest daughter Carmen (Martha Vickers). She was both spoiled, childish, irresponsible, and involved with pornographers who were blackmailing her (and her sister) for $5,000 regarding her pictures' prints and negatives. Marlowe learned that the General's friend (surrogate son) and companion Sean Regan had also mysteriously disappeared - and was likely to be dead. The private eye became sexually attracted to the older, feisty and sultry daughter Vivian (Lauren Bacall) when she became curious about Marlowe's investigation, but worried that he was digging too deep. In the twisting tale, the blackmailer, bookstore owner Arthur Geiger (Theodore von Eltz) was shot dead and shortly later, Sternwood's replacement chauffeur Owen Taylor was also found murdered. As the blackmail case progressed, Marlowe described his suspicions to gambler Eddie Mars (John Ridgely) that Carmen had killed her father's missing companion Sean Regan, when he refused her sexual advances. She murdered Regan out of jealousy (and unrequited love) over an imaginary relationship between Regan and Mars' wife Mrs. Mona Mars (Peggy Knudsen). [Note: Mona was discovered hiding out at Huck's Garage, to make it look like she had run away with Regan during their entirely manufactured affair.] At Vivian's request, Mars had covered up Regan's killing to "protect" her sister Carmen from guilt - and to prevent her sick father from any further suffering. Mars' cold-blooded hired killer Canino (Bob Steele), hid Regan's body and the deception was set up. Mars then blackmailed Vivian for money and sexual favors. Marlowe cleverly set up Mars to be killed by his own henchmen, allowing Marlowe to protect Carmen (who was sent "away" to an institution for psychiatric care) and Vivian by pinning the murder of Regan on Mars - and Marlow was also able to end up with Vivian.

The Blue Dahlia (1946), 98 minutes, D: George Marshall

Raymond Chandler's Oscar-nominated screenplay provided the who-dun-it script for this classic hard-boiled Alan Ladd/Veronica Lake noirish crime film. It was the third of four screen pairings between Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake. Director George Marshall combined various elements to produce a well-made noir, about a hard-nosed GI soldier returning from service who became entangled with a mysterious blonde when they were both faced with unraveling a murder. Its tagline was: "Tamed by a brunette - framed by a blonde - blamed by the cops!" Returning 28 year-old WWII veteran and naval flier Lt. Cmdr. Johnny Morrison (Alan Ladd) was one of three soldiers discharged from service and in Southern California. His buddies included Buzz Wanchek (William Bendix) (with a serious mental health disability) and George Copeland (Hugh Beaumont). At her luxurious Hollywood garden bungalow during a cocktail party, Johnny soon discovered that his boozing, unfaithful estranged wife Helen (Doris Dowling) had been promiscuous with LA's The Blue Dahlia nightclub owner Eddie Harwood (Howard Da Silva) during his absence. When the party broke up, Helen quarreled with Johnny, and then confessed that she lied to him about the death of their young son. He had not died from diptheria, but was killed in a DUI car-crash accident while she was driving - drunk. Johnny angrily pulled out his gun on her (he hinted: "That's what I oughta do, but you're not worth it"), but then he walked out on her while throwing his gun into an armchair before leaving the bungalow. Ironically, Johnny was hitchhiking with his suitcase and picked up in the rain by Harwood's wife, long blonde-haired wife Joyce (Veronica Lake), but remained anonymous to each other. She helped him leave town as the two shared a drive up the coast to Malibu and beyond, and after parting were not aware until the next morning that they both spent the night at the same beachfront motel, the Royal Beach Inn (in separate rooms). News on the radio arrived that Johnny's buddy Buzz was wanted for the murder of Helen - and that he also was presumed to be a prime suspect. He returned by bus back to Los Angeles, took an assumed name (Jimmy Moore) and rented a cheap hotel, while trying to clear his name (with some independent assistance from Joyce). Meddlesome bungalow motel house detective "Dad" Newell (Will Wright) was questioned by police and testified that he had heard Johnny fighting with Helen, and that he had witnessed Harwood later in the night enter her bungalow. The police also interviewed numerous other suspects, including Harwood and Buzz. Joyce was also considered as a possible suspect. In the conclusion, most of the suspects were assembled in The Blue Dahlia nightclub as the police authorities pressured Buzz to confess. The surprise killer was revealed to be disgruntled house detective 'Dad' Newell. He had attempted to blackmail Helen about her affair with Eddie, but when she refused to comply, he killed her. When Newell pulled out a gun after incriminating himself, he was startled when a door opened behind him and shot dead by the police Captain. The film ended as Johnny suggested continuing his relationship with Joyce.

Brief Encounter (1946, UK), 85 minutes, D: David Lean

David Lean's melodramatic romance was based on the 1936 Noel Coward one-act play (Still Life). It was a poignant, sensitively-told, restrained British story about forbidden passion in a brief platonic, extra-marital affair. It was the quintessential, desperate tale of unconsummated illicit love. The romanticism of the film was enhanced by Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 musical score. It told about two married strangers who had a chance meeting on the platform of the Milford Junction train station, and subsequently developed a forbidden romance. Although not known until further into the film, Brief Encounter opened in the past - as a middle-aged couple met and then parted for the last time. The same scene of their final moments was played out another time at the film's downbeat conclusion after an extended full flashback - filtered by the woman's subjective perspective in the last scene. The two English citizens were idealistic married local doctor, Dr. Alec Harvey (Leslie Howard) and middle-class suburban housewife and mother Laura Jesson (Celia Johnson), who found herself stuck in a loveless marriage. Their casual friendship and acquaintanceship involving casual weekly encounters soon turned into a romantic relationship and they fell in love. A planned tryst to consummate their affair was aborted. They agreed to separate and stop seeing each other when he took an assignment in another country - a medical journey to South Africa. During their final day together, they were interrupted by Laura's talkative and gossipy friend Dolly Messiter (Everley Gregg) during a painful, repressed goodbye as Alec gently placed his hand on her shoulder and disappeared forever. The anguished Laura attempted a near-suicide (with a mad, self-destructive urge signified by a tilted camera) when she jumped up abruptly from the table and rushed outside the tea room to the rail platform. Her internal state was externalized and stylized as disorienting and unbalanced. At the edge of the platform as the train screeched through, she contemplated throwing herself under the passing train, but lacked the courage to do so. In the final scene following their parting after such a brief encounter, her flashback ended as the film jumped from her standing at the doorway of the tea room, to a view of her seated in her armchair in her home - stuck back in her predictable and humdrum middle-class existence and routine. Dazed, disoriented, defeated (?) and jarred by memories of her passionate love affair, she was in the company of Fred Jesson (Cyril Raymond) - her unemotional but thankful husband ("Thank you for coming back to me").

Duel in the Sun (1946), 138 minutes, D: King Vidor

Although critically nicknamed "Lust in the Dust" by its detractors, director King Vidor's film remains one of the top box-office westerns - in inflation-adjusted dollars. [Note: In fact, Vidor quit and was one of eight directors and cinematographers.] The ambitious scandalous production from David O. Selznick was a "Gone With The Wind"- type grand western with an amour fou tale. This lurid Technicolor western, set in Texas in the 1880s at the Spanish Bit cattle ranch, was a sprawling, overheated melodramatic saga of sexual longing that was forced to cut nine minutes of its content before widespread release. The tale opened with the hanging execution of Scott Chavez (Herbert Marshall) (for the murder of his Indian wife and her lover). His unrefined, 'half-breed' gypsy daughter Pearl Chavez (Jennifer Jones) was left orphaned and without a home. Meanwhile, crippled Senator Jackson McCanles (Lionel Barrymore) ruled as the patriarch of the cattle baron family at the Spanish Bit Texas cattle ranch. His long-suffering, weak wife was Laura Belle McCanles (Lillian Gish), and they had two "Cain and Abel" archetypal sons: moderate, kind-hearted and cultured Jesse (Joseph Cotten) who had studied law, and hot-tempered, gun-slinging and amoral Lewt (Gregory Peck). Pearl was taken in to live at the ranch by Scott's second-cousin and ex-sweetheart/lover Laura. At the same time, McCanles and other ranchers had joined forces to defend their lands from encroachment by the railroad companies. Pearl was soon caught in a very lethal and destructive love triangle between the two McCanles sons. In the violent orgiastic, melodramatic ending, Pearl and Lewt shot each other to the death at Squaw's Head Rock and died in each other's arms.

Gilda (1946), 110 minutes, D: Charles Vidor

Director Charles Vidor's semi-trashy, steamy crime drama was known for the erotic strains of the strange, tawdry, aberrant romantic triangle (menage a trois) between the three main characters. The film-noirish screenplay by Marion Parsonnet (and adapted by Jo Eisinger), was taken from an original story by E. A. Ellington. The film's themes included implied impotence, misogyny and homosexuality, although only suggested with liberal euphemisms and innuendo to bypass the Production Code. The complex, eccentric, perverse, and cynical tale was in keeping with the prevailing attitudes of the American post-war era, playing upon US political paranoia of German-Nazi war criminals who escaped and assumed new identities in South America. [Note: Another similar plotline was found in Hitchcock's Notorious (1946)]. The titular femme fatale Gilda Mundson Farrell (Rita Hayworth) was put into the care and keeping of her ex-lover (a gambler and small-time hood) and bodyguard Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) - the right hand man of her disagreeable South American casino-owning, mobster husband Ballin Mundson (George Macready). The sultry Gilda performed a seductive striptease (to the tune of Put the Blame on Mame) when onstage, she removed long black satin gloves from her arms. When Mundson disappeared and was presumed dead, Gilda and Farrell resumed their dangerous affair, while Farrell ran the casino - but then Mundson vengefully returned.

Great Expectations (1946, UK), 118 minutes, D: David Lean

This definitive British drama was based on Charles Dickens' novel (and the first of two films director David Lean adapted from Dickens' works), with deserved Oscar wins for its detailed set design and black-and-white cinematography. It has long been considered one of the best adaptations ever made of a Dickens novel, and one of the finest British films of all-time. It told about an orphaned British boy befriended by a mysterious benefactor, and later becoming a gentleman of means (a man of "great expectations"). It began with the voice-over: "My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name, Phillip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than 'Pip'. So I called myself Pip and came to be called Pip." Then it proceeded to a very memorable, gloomy opening sequence of young Pip (Tony Wager) meeting escaped convict Abel Magwitch (Finlay Currie) in a graveyard. Pip then served as a hired playmate to a young adoptive daughter named Estella who was cared for by a wealthy, eccentric, and mysterious older woman in an dilapidated estate. Later, Pip was given a financial fortune (an allowance and funds for education) from an unknown source (not Miss Havisham!), and opportunistically became wealthy and cultured, although snobbish. All of the Dickens' characters were faithfully portrayed - John Mills took the role of the older Pip and Jean Simmons as the young Estella, Martita Hunt as Miss Havisham, and Francis L. Sullivan (who played the same role in the 1934 Hollywood version) as Mr. Jaggers, Miss Havisham's lawyer.

It's A Wonderful Life (1946), 129 minutes, D: Frank Capra

Director Frank Capra's sweet-natured, sentimental, inspirational classic drama was about a near-suicidal man learning the value of his existence. A charitable, hard-working philanthropist George Bailey (James Stewart), forced to remain in a small town by unpredictable circumstances, became depressed after an accidental financial disaster at his loan company had benefited the miserly Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore). George was on the verge of committing suicide and wishing that he had never been born - when his crusty-but-lovable guardian angel Clarence (Henry Travers), who was desperately trying to earn his wings, showed up to give him a tour of his town without his presence (Bedford Falls had become the decadent and hellish Pottersville), showing him how important he'd been to the lives of his loved ones. Moral courage, small-town American life, civic cooperation, and family love were glorified while corporate greed and selfishness were condemned, climaxed by the man's rescue during an idyllic Christmas card finale. Clarence earned his wings and George learned that wealth was measured in love and friendship.

The Killers (1946), 102 minutes, D: Robert Siodmak

Director Robert Siodmak's classic, definitive film noir, taken from a short story by Ernest Hemingway, was told in eleven taut flashbacks after a bravura opening murder sequence. The film's main musical theme (with a rising and falling dum-de-dum dum) from composer Miklos Rozsa was later borrowed for the opening sequence of TV's Dragnet. Two hit men Al (Charles McGraw) and Max (William Conrad) entered a greasy-spoon diner in Brentwood New Jersey, asking the manager about Ole 'Swede' Andersen (Burt Lancaster, in his film debut) - a gas station attendant. The doomed 'Swede' (an ex-boxer), who had been hiding in town under an alias for six years, was warned in a nearby boardinghouse. Indifferent, he expected their arrival and calmly, passively awaited their deadly approach. Insurance investigator Jim Reardon (Edmond O'Brien) pieced together and unraveled the plot and reconstructed the life of the victim through interviews and detective work. He discovered a complex tale of crime and treacherous betrayal - all revolving around a beautifully-glamorous, mysterious, double-crossing femme fatale Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner) - who sang "The More I Know of Love."

A Matter of Life and Death (1946, UK) (aka Stairway to Heaven), 104 minutes, D: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Reminiscent of other heavenly fantasies, including Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) and Down to Earth (1947), this was one of the most innovative, visually-dazzling (from cinematographer Jack Cardiff), literate, and audacious films ever made by the extraordinary writer/producer/director team of the Archers production company: Powell and Pressburger. The film was an extravagant and extraordinary fantasy in which WWII RAF pilot and squadron leader Peter David Carter (David Niven) must abandon his fiery bomber (returning from a raid over Germany) without a functional parachute. Knowing his fate was doomed, he nonetheless fell deeply in love with British-based, WAC radio operator and ground controller June (Kim Hunter) as they shared a few last words. In a film that continually begged the question, what was real and what was imagined, he awakened unharmed on a beach after falling to his 'death', due to errors made by heavenly emissary Conductor 71 (Marius Goring) in the fog. During brain surgery to rid him of alleged hallucinations, his spirit was put on trial -- and he had to justify his continuing existence on Earth to a panel of heavenly judges in a celestial court (with God (Abraham Sofaer) as his judge, recently-deceased friend Dr. Frank Reeves (Robert Livesey) as his defense lawyer, and Abraham Farlan (Raymond Massey) as the prosecutor). He had to convince them that he should survive and wed his romantic sweetheart June. In a bold stroke, the Heavenly sequences were filmed in black-and-white, while the Earthbound scenes were in vibrant, ravishing Technicolor. The film used various then-revolutionary film techniques such as time-lapse photography, mixing monochrome and color in the same shot, and background time-freezes when a spirit left the body, reminscient of The Matrix (1999). One shot typified just how different the film was -- a point-of-view (POV) shot from within an eyeball during brain surgery. The most spectacular dream sequence was the slow ascent to heaven on a giant stairway, and the film's most memorable image was of a single, glittering love tear on a red rose petal.

My Darling Clementine (1946), 97 minutes, D: John Ford

My Darling Clementine was one of John Ford's greatest westerns. This semi-historical account was based on the famous 1881 O.K. Corral gunfight - inevitably visualized in the conclusion. The title credits were underscored by the singing of the folk song "(Oh My Darling) Clementine" by a cowboy chorus. It was the tale of the four Earp brothers - in the early 1880s, during a cattle drive through Arizona enroute to California. They had the first of many encounters with Old Man Clanton (Walter Brennan) and his Clanton gang of scurrilous gunfighters - who met with one-time outlaw gunslinger Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) on the trail and told him of the nearby town of Tombstone, AZ in 1882. Three of the four Earp brothers ventured to the uncivilized, wild town of Tombstone that evening - a lawless town (without a marshal) - evidenced in the early scene when Wyatt Earp's haircut with a barber (Ben Hall), a symbol of advanced civilization on the frontier, was interrupted by a shooting outdoors by drunken Indian Charlie (Charles Stevens) (Wyatt: "What kind of a town is this anyway? Excuse me ma'am. A man can't get a shave without gettin' his head blowed off") - and Wyatt was forced to subdue the man. When the Earps returned to their campsite, Wyatt suspected that the Clantons had rustled the Earp cattle and murdered his younger brother James Earp (Don Garner). Wyatt decided to seek revenge, by becoming the town's dedicated, law-abiding marshal (and making his surviving brothers his deputies), to clean up the rowdy frontier town where the killers of his brothers, led by Old Man Clanton, had fled and ruled. Wyatt developed a friendship with hot-tempered, well-educated gambler, gunfighter and saloon chief Dr. John Henry "Doc" Holliday (Victor Mature), originally a cultured Bostonian, who was suffering from TB (or "consumption"). His mistress was hot-blooded Mexican saloon dancer-singer Chihuahua (Linda Darnell). Earp cultivated a romance with Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs), the town's new school teacher. She was "Doc's" former ex-lover/fiancee from Boston, who had arrived in town to locate him, but he spurned her. Earp majestically escorted Clementine to a church service (dedicating the laying of the foundation of a new church to be built), and the church's open-air social dance - a fundraiser. The man who killed Wyatt's brother James - Billy Clanton (John Ireland), fearing that Chihuahua would implicate him in the murder of James, shot and mortally-wounded Chihuahua, and despite efforts of "Doc" to save her with surgery, she soon died. After killing Billy, Wyatt's brother Virgil Earp (Tim Holt) was cold-bloodedly shot in the back by Old Man Clanton at their homestead. After the climactic shootout against the Earps at the OK Corral that decimated the Clantons, Doc Holliday's affliction weakened him and made him vulnerable, and he died during the shoot-out. At the film's end -- Earp bid goodbye to Clementine before riding off away from the camera toward the rock monuments in the distance in the last image: ("Ma'am, I sure like that name - Clementine") - he was leaving town and joining up with his brother Morgan Earp (Ward Bond).

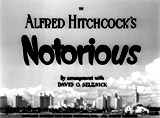

Notorious (1946), 101 minutes, D: Alfred Hitchcock

This was Hitchcock's ninth Hollywood film - a highly-acclaimed, post WWII noirish spy thriller/romance set in Brazilian South America. An alluring, alcoholic playgirl Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman), the daughter of a convicted Nazi agent, was reluctantly exploited and drafted by the CIA to become a US government agent and secretly infiltrate into a shady group of Axis Germans. Watchful American agent Devlin (Cary Grant) turned chilly toward her, uncertain of her love and loose-living past during a cruel love affair. To spite him when Devlin didn't protest her marriage, she wed her Nazi espionage target Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), a former friend of her father's, to acquire access to information, including the MacGuffin (uranium in wine bottles) in his wine cellar. Trapped in her enemy's home, where her husband was oppressed by his cold, domineering mother Mme. Sebastian (Leopoldine Konstantin), Alicia was slowly poisoned with arsenic and in mortal danger until rescued by guilt-ridden Devlin. The film featured the most famous marathon screen kiss in film history, the zoom shot toward the wine cellar key, the wine cellar sequence, and the staircase-descending finale.

Paisan (1946, It.) (aka Paisà), 120 or 134 minutes, D: Roberto Rossellini

This important neo-realistic Italian docu-drama was co-written by director Rossellini and Federico Fellini, and filmed in an authentic, documentary style with improvisational dialogue. It was an extremely powerful compilation of six episodes or vignettes - depicting the Allied invasion and liberation of Italy (from Sicily to Venice) during WWII, from July 1943 to the winter-spring of 1944. It surveyed a small group of people affected by the war on a day-to-day basis: a non-English-speaking Sicilian female (Carmela Sazio) guarded in a cave by American GI Joe (Robert Van Loon), black MP Joe (Dots M. Johnson) and his street urchin companion Pasquale, a love-sick American soldier Fred (Gar Moore) in Rome mistakenly believing that his dream girl Francesca (Maria Michi) wasn't a prostitute, an American nurse (Harriet White) and her wounded and dying partisan leader boyfriend (Gigi Gori), the sequence in a Franciscan monastery involving three Army chaplains of different faiths and the withdrawn monks, and the final action sequence at the Po River between the partisans and OSS men fighting the Germans.

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), 113 minutes, D: Tay Garnett

Director Tay Garnett's stylish moody adaptation of James M. Cain's 1934 torrid crime melodrama novel about the murderous effects of lust, told in flashback, was one of the best film noirs ever made. [Note: It was the third adaptation of Cain's novel, following Pierre Chenal's Le Dernier Tournant (1939, Fr.) and Luchino Visconti's Ossessione (1943, It.). Another modern US remake was Bob Rafelson's The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981) starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange.] Handsome hitch-hiking drifter Frank Chambers (John Garfield) was hired at the California roadside Twin Oaks diner/restaurant as a handyman by kindly, middle-aged, alcoholic proprietor Nick Smith (Cecil Kellaway). He was mostly interested in getting to know Nick's sizzling, lustfully white-hot (and unhappy), platinum-blonde waitress wife Cora (Lana Turner). The slow-burning fuse of sexual passion between Frank and tawdry adulteress Cora was first manifestly evident when they decided to run away and elope, but they decided to return. Over time, they came to the belief that the only way to be together was to plot the 'accidental' death of her husband to live off the inheritance. The murderous couple's first clumsy attempt at a fatal bathtub accident failed when a cat tripped the power lines and aborted the plan. Their plottings became more intense when Nick threatened to sell the diner and move with Cora to Northern Canada to live at his invalid, paralyzed sister's home. Their second plan to kill Nick was to get him drunk and then stage an automobile accident at Malibu Lake. They proceeded to ply Nick with liquor before clubbing him and pushing his car off a cliff. Slimy District Attorney Kyle Sackett (Leon Ames) was hot on their trail, and used a strategy of pitting the two against each other to draw convictions. After Frank (to avoid becoming Cora's accomplice) was tricked into signing an official complaint against Cora, alleging that she tried to kill both him and Nick, Cora also confessed and admitted to the charges but was later released on lesser charges of manslaughter. Although the couple didn't fully trust each other (and would ultimately be undone by their own uncontrollable, calculating natures), the two were married for respectability's sake. During Cora's week-long trip to visit her ailing mother in Iowa, Frank engaged in a brief affair with Madge Gorland (Audrey Totter) that was discovered by Cora upon her return. Cora also divulged that she was pregnant. During a moonlight swim, Cora dramatically threatened suicide, but Frank saved her from drowning and the two decided they truly loved each other. As they drove home before a fatal automobile crash, Cora admitted before her death: "When we get home, Frank, then there'll be kisses, kisses with dreams in them. Kisses that come from life, not death." Frank was convicted of Cora's murder and sentenced to be executed. A note was found written earlier by Cora that revealed her true love for Frank, but it also showed that they had plotted Nick's murder together. They would both pay a price for their misdeeds, even after they had both evaded charges for killing Nick. On Death Row, although Frank in his own mind was absolved of Cora's death - "the postman always rings twice" - he was led to his execution for Nick's death (and for committing adultery), after telling the priest Father McConnell (Tom Dillon): "Somehow or other Cora paid for Nick's life with hers. And now I'm going to. Father, would you send up a prayer for me and Cora? And if you could find it in your heart... make it that we're together, wherever it is."

The Razor's Edge (1946), 146 minutes, D: Edmund Goulding

This outstanding romantic (melo)-drama by director Edmund Goulding (and produced by Darryl F. Zanuck for 20th Century Fox) was taken from W. Somerset Maugham's 1944 novel (adapted by scriptwriter Lamar Trotti). Although long, gloomy and rambling, it was about the search for life's intellectual and spiritual meaning - and enlightenment. In the film, idealistic, wealthy young Larry Darrell (Tyrone Power) served in the war as a pilot and narrowly escaped death when a comrade saved him. His entire being was shaken, traumatized and disillusioned by the horrors of WWI, and he restlessly set out to seek truth and goodness for the remainder of his life. He explained the rationale for his search: "It was the last day of the war, almost the last moment. He could have saved himself, but, he didn't. He saved me, and, died. So he's gone and I'm here, alive. Why? It's all so meaningless! You can't help but ask yourself what life is all about. Whether there's any sense to it or whether it's just a stupid blunder!" In Chicago in 1919, wealthy, upper-class, social-climbing, worldly beauty Isabel Bradley (Gene Tierney) offered him love and stability as his fiancee, but she agreed to postpone their marriage so Larry could first travel to Paris to find himself. Larry would be mentored by Isabel's snobbish uncle Elliott Templeton (Clifton Webb), a wealthy bachelor, during his time in European society. In Paris, however, Larry rejected Templeton's offer and became part of a "Lost Generation" of seekers that renounced wealth. He moved into very modest accommodations on the Left Bank. About a year later, Isabel visited Larry in Paris - and decided that she couldn't marry him, due to her concerns about his lack of desire for ambition, wealth and status. She broke off their engagement, but then just before leaving France, she set about to seduce Larry into having sex, and then would later blackmail him into marriage by feigning pregnancy. However, she couldn't carry through with her devious plan, and shortly later returned to Chicago and married millionaire stockbroker Gray Maturin (John Payne) to insure a life of luxury and elite power for herself. Larry continued to pursue his quest for truth by first working as a coal miner, and then taking a pilgrimage to the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, where he was taught the truths about life through an old mystic Hindu guru, Holy Man (Cecil Humphreys) ("As long as man sets his ideals on the wrong objects, there can be no real happiness. Until men learn it comes from within themselves"). He learned that the path to salvation was as difficult to pass over as the sharp edge of a razor. Larry eventually found enlightenment, peace, personal serenity and freedom, and was ready to return to the world. When he returned almost a decade later to Paris in 1931, he learned about the fates of his former acquaintances - many of whom had suffered challenging experiences. Strong-willed Isabel's husband had lost his wealth in the stock market crash of 1929 and suffered a nervous breakdown, with frequent debilitating headaches. Isabel and Gray Maturin were now living in Paris in Elliott's apartment (while he resided in the Riviera). Larry was also reunited with former childhood friend Sophie Nelson (Oscar-winning Anne Baxter) whose husband Bob MacDonald (Frank Latimore) and child were killed in an automobile accident. Sophie was discovered in a working-class bistro, degraded and wracked by alcoholism, drug use and prostitution (for an abusive pimp) in a lower class district of Paris. With his efforts, Larry was able to bring the unstable widow back to sobriety and soon became engaged to marry her. However, Isabel was resolute on reigniting her relationship with Larry, and jealously conspired to cause Sophie's self-destructive demise by tempting her to begin drinking again with a bottle of expensive Hungarian liqueur. Sophie henceforth disappeared into the Parisian underworld, was found in an opium den, and within a year, Sophie's victimization ended with her murder in Toulon. Larry blamed Isabel for deliberately encouraging and tempting Sophie, although Isabel claimed she did it to save Larry and as a way to test Sophie's strength. Larry refused to reconcile with Isabel and walked away from her - forever. He announced his intention to return to America by supporting himself as a common laborer. Isabel finally realized: "I've lost him for good." Isabel asked the film's detached W. Somerset Maugham character (Herbert Marshall), a British novelist, what he thought that Larry had accomplished, and was told, in the film's final lines of dialogue, that Larry had obviously found the key to true happiness and goodness: ("His America will be as remote from yours as the Gobi Desert....My dear Larry has found what we all want and very few of us ever get. I don't think anyone can fail to be better and nobler, kinder for knowing him. You see, my dear, goodness is after all the greatest force in the world, and he's got it." The last shot was of Larry on the deck of a ship in the pouring rain, working as a lowly deck-hand to pay for his passage home.

The Spiral Staircase (1946), 83 minutes, D: Robert Siodmak

Director Robert Siodmak's classic, old-fashioned haunted house horror film with Gothic (and Hitchcockian) elements involved a threatened female and a serial killer (who specialized in killing imperfect, physically-flawed, handicapped or "afflicted" women). [Note: The set was the house from Orson Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).] The stylish, suspenseful, and taut thriller - and frightening psychological drama-mystery, was based on crime writer Ethel Lina White's 1933 novel "Some Must Watch," and was remade as The Spiral Staircase (1975, UK) with Jacqueline Bisset, Christopher Plummer, and Mildred Dunnock. Set in 1916 in a small town in New England (Vermont), the film opened with the third murder committed by the killer (who strangled a paraplegic female in her hotel room) in the neighborhood. A young mute servant-caretaker Helen Chapel (Dorothy McGuire) was hired to assist a wealthy, widowed, bed-ridden invalid matron Mrs. Warren (Ethel Barrymore) with powers of perception in a large spooky mansion (with many secret doors and heavy draperies, and of course, a circular staircase) - where the killer was hiding in the shadows within the house. An atmosphere of terror in the old dark mansion was intensified with a raging storm outside, high contrast or light and dark shadows, a spiral staircase, a view of feet behind a heavy curtain, gusts of wind, flickering candlelights, and creaking doors. The local bachelor doctor, Dr. Parry (Kent Smith), Mrs. Warren's local physician and one of Helen's love interests, believed that her inability to speak had been trauma-induced (from witnessing a house fire that killed her parents) and was possibly reversible. He was planning to take her to Boston to help her work through her psychological issues. Two other suitors (rival step-brothers) who lived in the house included Mrs. Warren's anti-social stepson - scholarly biologist Professor Albert Warren (George Brent), and her real younger son - the irresponsible, impudent and womanizing Steven Warren (Gordon Oliver), who recently returned from living abroad. He was involved in a brief affair with Albert's live-in, bespectacled assistant-secretary Blanche (Rhonda Fleming). The young, tormented and victimized mute Helen soon came to believe that she would be the killer's next victim, after Blanche was attacked and murdered in the basement. In the exciting conclusion, it was implied that Steven had murdered Blanche, and Helen (who suspected him) locked him up in a closet, only to then realize that the real killer was Professor Warren. The defenseless Helen screamed at her extreme moment of peril on the spiral staircase when chased by the Professor, and was saved by Mrs. Warren who emerged from her bedroom, staggered out and shot her stepson multiple times in the chest, and then fainted (died?) in Steven's arms. In the suspenseful climax, now with restored speech, Helen then uttered her first words since childhood with a phone call to an operator, asking for Dr. Parry: ("1-8-9...Dr. Parry...Come...It's I, Helen") - the film's final line of dialogue.

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), 116 minutes, D: Lewis Milestone

This sordid, noirish, B/W melodrama told about three childhood friends who were brought together 18 years later for a climactic denouement regarding a murderous and guilty secret from the past, in the Pennsylvania town of Iverstown. The film opened in 1928 with young heiress Martha Ivers (Janis Wilson as a girl) bludgeoning (with a cane) her domineering, mean-spirited, tyrannical, wealthy Aunt Ivers (Judith Anderson) to death (on a flight of stairs, where afterwards, she tumbled to her death) during a raging thunderstorm - Martha sought revenge for her hard-hearted Aunt's caning to death of her beloved kitten named Bundles. At the time, Martha had repeatedly been planning to run away with her young, street-smart, independent-minded boyfriend Sam Masterson (Darryl Hickman as a boy). The murder was thought to have been witnessed by two boys: Sam, who fled town (and joined a circus), and by prim, and bespectacled Walter O'Neil (Mickey Kuhn as boy) who was at Martha's side looking on. The weak-willed Walter was urged by Martha to lie about the killing to conceal her guilt. In exchange for their help in denying Martha's involvement, Walter's scheming father Mr. O'Neil (Roman Bohnen), Martha's greedy tutor, blackmailed Martha into marrying Walter (so that he could acquire her inherited wealth and influence), while an innocent man years later was accused, condemned and executed for the murder of Martha's aunt. The love triangle clashed when they were brought together again years later in 1946. The three were Martha Ivers (Barbara Stanwyck as adult) - a domineering, single-minded, predatory, self-interested, and determined femme fatale where she dominated everything, Walter O'Neil (Kirk Douglas as adult, in his film debut), lovelessly married to Martha, an alcoholic district attorney in the steelworks town of Iverstown, and Sam Masterson (Van Heflin as adult), Martha's former beau (who she was still attracted to), a decorated wartime soldier and gambler. Passing through Iverstown, Sam was forced to remain in the town after crashing his car into a signpost. Martha (and Walter) feared Sam's knowledge of the awful crime and would try to blackmail them, although at a crucial point in the film, he admitted that he did not witness Aunt Ivers' death ("I wasn't there. I left when your Aunt came into the hallway. I didn't want to stick around. I was in enough trouble as it was. I never saw what happened. I never knew until tonight about your Aunt or that man. The one they hung. The man that you and Walter killed"). [Note: In the film's major sub-plot, Sam tried to help a new acquaintance in town, young, sexy and pretty Antonia "Toni" Marachek (Lizabeth Scott), who was on parole (after charges of theft), but was arrested for violating her probation (she was supposed to leave town immediately). Sam appealed to DA Walter to request his influence in her case. Although Toni betrayed Sam and set him up for a beating, she was under pressure by Walter to do so, and was ultimately forgiven by Sam.] Martha, who had never given up her love for Sam, decided to seduce him and then urged him to heartlessly kill her drunken husband after he fell down the ubiquitous staircase and was unconscious: ("Now, Sam. Do it now. Set me free. Set both of us free...Oh, Sam, it can be so easy"). Sam refused to comply with her: ("Now I'm sorry for ya....Martha, you're sick...You're so sick you don't even know the difference between right and wrong....I've never murdered"). After Sam declined to murder Walter and even helped him to revive, he was prepared to walk out of the mansion, when Martha threatened to shoot Sam as an intruder - in "self defense" - ("We can't let him go, can we?...We'd be fools to let him go, knowing so much about us"), but she couldn't pull the trigger on him and shoot him in the back. As he left, he told them: "I feel sorry for ya, both of ya." The shock double-suicide ending included Martha's death when she pulled the trigger on herself as her jealous and drunk husband Walter held a gun to her stomach during a deadly embrace - and then with her draped limply in his arms, Walter shot himself to death. Sam witnessed the two deaths through a window, as he stood outside the mansion, before driving off with Toni westward to get married (Sam to Toni: "Don't look back, baby. Don't ever look back. You know what happened to Lot's wife, don't ya?").

The Stranger (1946), 95 minutes, D: Orson Welles

This impressive film noir starred and was directed by Orson Welles - it was his first suspense-thriller. Keen-minded United Nations War Crimes Commission government agent-investigator Mr. Wilson (Edward G. Robinson) was on the trail of Nazi war criminal, fugitive agent Franz Kindler (Orson Welles). In the small and sleepy Connecticut town of Harper, the deceitful Kindler was posing as Charles Rankin, a respectable New England prep school teacher, engaged to marry Mary Longstreet (Loretta Young) - the daughter of respectable Supreme Court Justice Adam Longstreet (Philip Merivale). Mary was unaware of her fiancee's notorious past as the mastermind of the genocidal Holocaust. To prevent being exposed, Kindler strangled his former associate Meinike (Konstantin Shayne). To get to his quarry in a tense cat-and-mouse game, Wilson (posing as an antiques dealer) had to convince the suspicious Mary of her fiancee's crimes, before he eliminated her too. In the exciting conclusion, topped by a chase-finale on a church belfry tower, Mary discovered Rankin's plot to kill her and dared him - and when prevented and pursued, he fell to his death.

To Each His Own (1946), 122 minutes, D: Mitchell Leisen

This was star Olivia de Havilland's first screen role after winning a landmark Supreme Court case against Warners, reducing exploitative studio control of actors to seven years. It was similar in plot to Edmund Goulding's The Old Maid (1939) with Bette Davis. The superior, sentimental romantic melodrama (or women's "weepie") was told in flashback by an unwed mother (now a middle-aged American expatriate, and a fire-watch warden in London during an air-raid beat) who encountered the son she had given up for adoption many years earlier. Miss Josephine 'Jody' Norris (Best Actress-winning Olivia de Havilland) recalled a passionate, small-town love affair in Pierson Falls in upstate New York with Captain Bart Cosgrove (John Lund in his debut film), a pilot who presumably died during action in WWI (the Great War). She was painfully forced to give up her son for adoption to another family to avoid scandal. Her son was taken in by Corinne (Mary Anderson) and Alex Piersen (Phillip Terry) when Jody maneuvered herself out of the right to call the child her own. Afterwards, Jody spent years devoted to a successful cosmetics business, while her grown son American Lieutenant Gregory 'Grigsy' Pierson (also John Lund) only knew her through casual contact and presents (given by "Aunt Jody" - known as a friend of his "mother"). When he visited and revealed his attachment to girlfriend Liz Lorimer (Virginia Welles), Jody's aristocratic confidant and love interest Lord Desham (Roland Culver) helped their romance lead to marriage, and broadly hinted to Gregory the identity of his biological mother, in the tear-jerking happy conclusion. Liz also tipped off Grigsy: "Anyone would have thought you were her only son" - he then approached his mother on a dance floor and asserted: "I think this is our dance, Mother."

The Yearling (1946), 134 minutes, D: Clarence Brown

Director Clarence Brown's beautiful and sensitive film was based on the 1938 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. It was remade for TV in 1994. The inspirational family-oriented, coming-of-age dramatic story was about a young boy who matured after confronting the harsh realities of life - accepting a final goodbye to his beloved animal friend. In the late 1870s, somber, overprotective and stern Orry (Jane Wyman) and kind-hearted, understanding Penny Baxter (Gregory Peck) lived in the remote Florida wilderness (Baxter's Island) where they eked out a living on their farm. Sole surviving child, fresh-faced and pleasant Jody (Claude Jarman, Jr. in his screen debut), a lonely 12 year-old son, longed to have a pet to keep him company. Due to dire circumstances, Penny was compelled to orphan a fawn - after being bitten by a rattlesnake, he killed a doe to use its organs to release the poisonous venom. The yearling fawn, named Flag, grew closer and attached to Jody, but problems developed - it ate the pioneer family's hard-won crops of tobacco and corn, and the boy was forced to accept a painful, heart-wrenching decision. Rather than shoot the yearling, Jody released him into the woods. Tough-minded Orry shot and wounded Flag, and tearful Jody finished him off. Jody ran away, but then returned home after three days, to his relieved parents.